Gallery

Photos from events, contest for the best costume, videos from master classes.

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

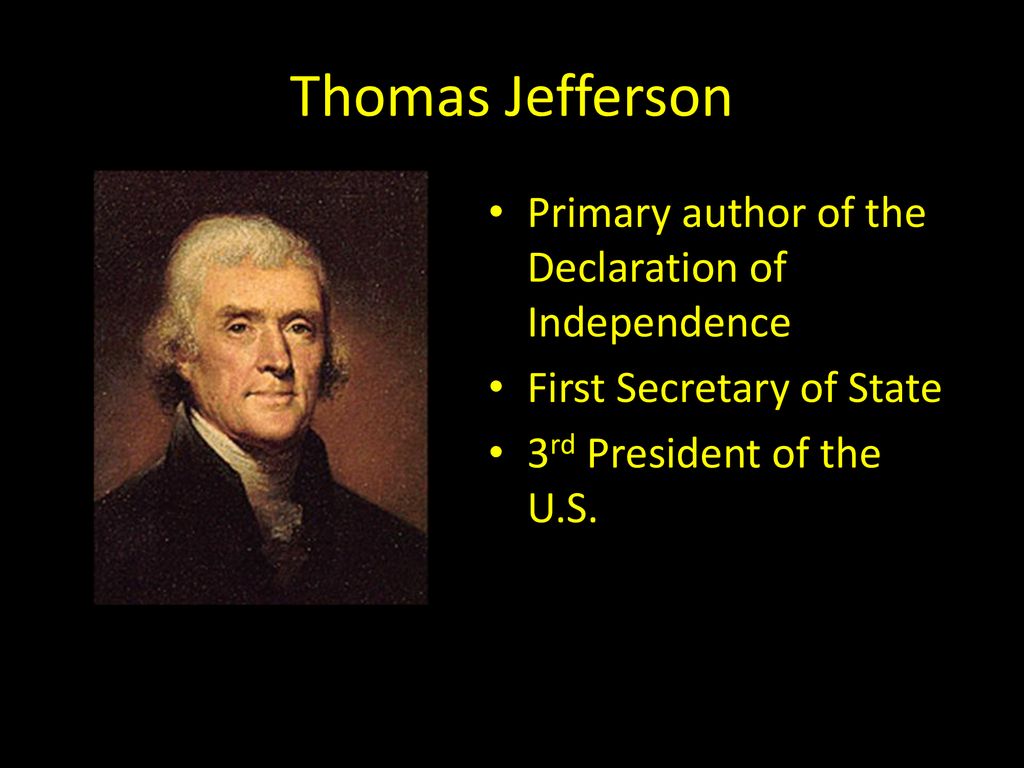

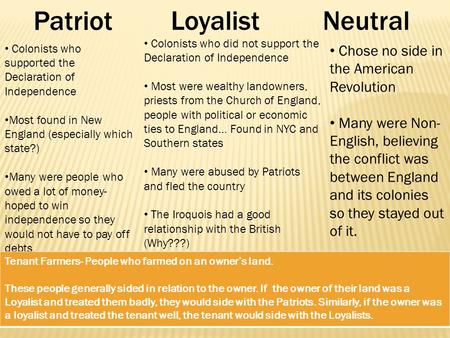

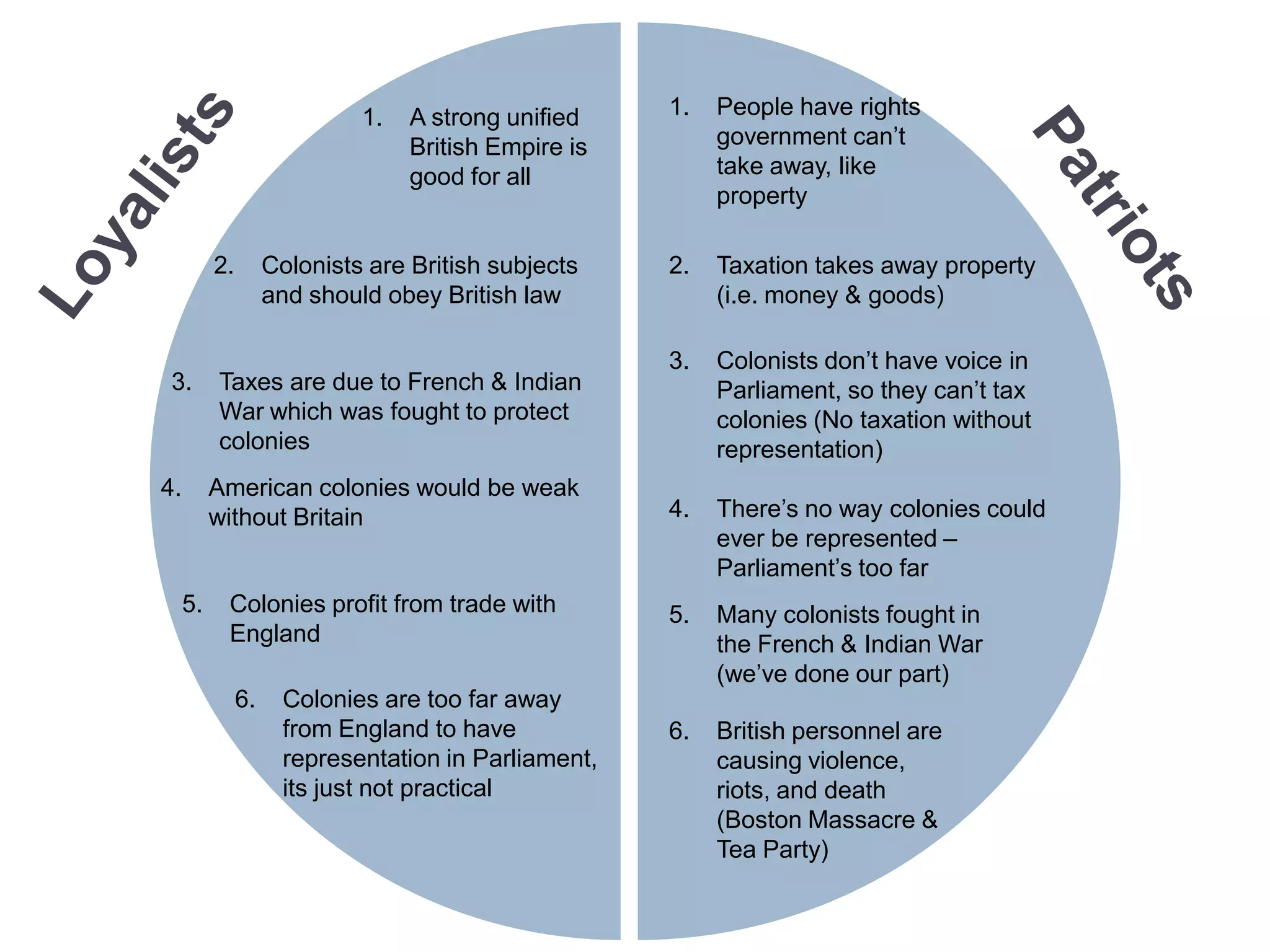

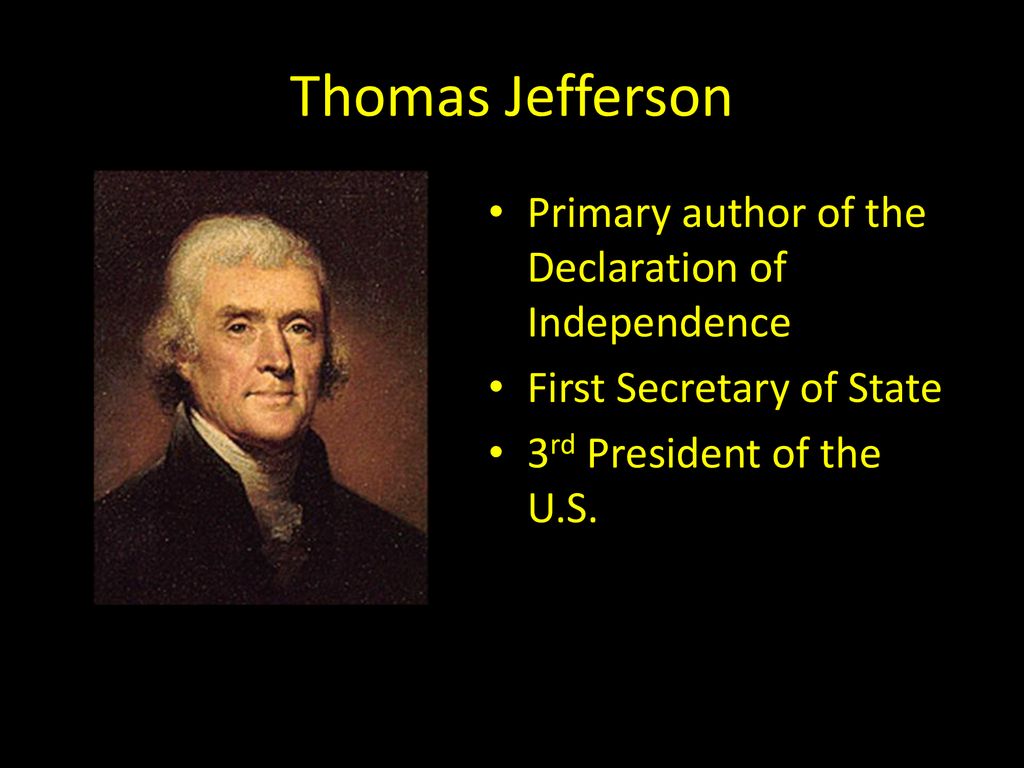

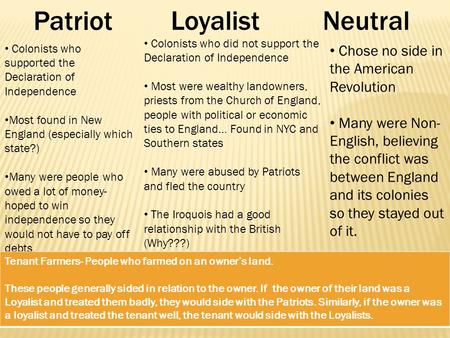

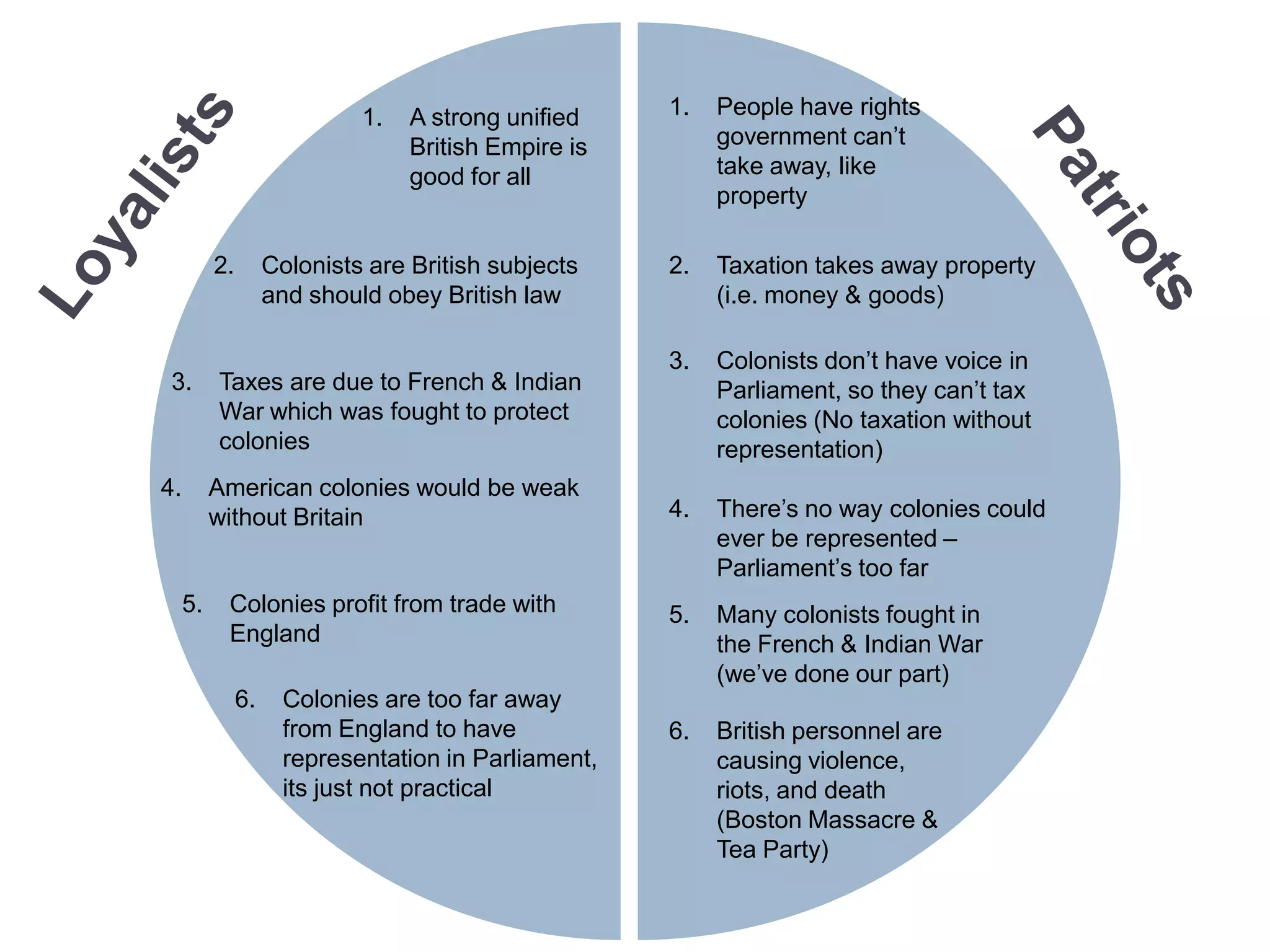

Their research suggests Loyalists were better attuned to trends across the Atlantic than Patriots, whose positions reflected arguments made decades before by opposition groups in England. Reliance by Patriots on those older arguments revealed an especially wide conceptual gap with British opinion and Loyalists on legal arguments. Prior to the formal beginning of the American Revolution, many patriots were active in groups including the Sons of Liberty. The most prominent patriot leaders are referred to today as the Founding Fathers, who are generally defined as the 56 men who, as delegates to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, signed the Declaration of Independence. Patriots included a cross-section of Learn about Patriots and Loyalists during the Revolutionary War. One side wanted independence while the other wanted to remain part of Britain. During the American Revolution, some colonists, known as Loyalists, remained loyal to the British monarchy while others, known as Patriots, rose out in rebellion against it. By comparing and contrasting these two artworks, we can examine both sides of the dispute over independence and how the issue directly affected the lives of those involved. Those who rebelled against the control and oppression of Britain were termed Patriots. Banner image: Original Declaration of Independence, parchment, 1776 (detail); on exhibit in the Rotunda of the National Archives, Washington, DC. Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Hoai Bui Loyalists Vs Patriots Hour 3 America’s declaration of independence was a huge event in our nation's history. It freed us from Great Britain and made us independent. During the time, there were two distinct political groups within the colonies; the Loyalists and the Patriots. Loyalists, like their name states, were loyal to Britain and believed that the colonies were better off being The Glorious Revolution had been justified as Protestant resistance to a tyrannical Catholic king. That model of a successful transfer of power very much appealed to the Patriots in their own resistance to a king“whose character” (in the words of the Declaration of Independence) “is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant.” After years of unrest, fighting broke out in 1775. A year later, the Declaration of Independence was signed. Propaganda in support of independence split the colonists into two groups: patriots and loyalists. Patriots were active supporters of independence, and willing to fight for it. In many ways the Revolutionary War was a civil war between citizens of a divided nation. The fight during the Revolutionary War was between those people who remained loyal to Great Britain (the Loyalists) and those people who desired independence from Great Britain (the Patri-ots). The Loyalist Declaration of Independence published in The Royal Gazette (New York) on November 17, 1781 (Transcription provided by Bruce Wallace and posted on The On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies.) The Declaration of Independence formalized the Patriots' quest for independence, which Loyalists rejected, further polarizing loyalties. The Battle of Saratoga, a pivotal Patriot victory, not only boosted Patriot morale but also secured French support, altering the dynamics of the war. The Declaration of Independence was a turning point that decided for each of these groups who they would support in the Revolution. Loyalists were typically upper class, Patriots typically middle class, and neutrals usually lower class. Those who favored independence from Great Britain were called Patriots. Those who wished that the Colonies remain tied to Great Britain were known as Loyalists. Americans who elected not to choose a side were called Neutrals. Colonists had various reasons for whichever side that they chose. Loyalists comprised 15-20% of the colonial population during the Revolutionary War. “Patriots,” as they came to be known, were members of the 13 British colonies who rebelled against British control during the American Revolution, supporting instead the U.S. Continental Congress. As a loyalist, the Declaration of Independence is viewed as unjustified. The taxes imposed by the British, though unfair, didn't implicitly justify a complete revolution. The loyalists favored evolution over revolution, making the decision to declare independence impulsive and costly. The current thought is that about 20 percent of the colonists were Loyalists — those whose remained loyal to England and King George. Another small group in terms of percentage were the dedicated patriots, for whom there was no alternative but independence. Often lost in a study of the Revolution are the "horrors of civil war" among Americans themselves—among supporters of independence (Patriots/Whigs), opponents (Loyalists/Tories), and the ambivalent Americans who were angry with Britain but opposed to declaring independence. Both documents stressed the absolute necessity of independence: that no other option was left to preserve American rights and liberty. And each document addressed the front-and-center question: How do we justify this unprecedented action to our fellow Americans, Britain, and the world? A poem on Common Sense: Hannah Griffitts, "Upon reading a Book entitled Common Sense," 1776. From a well-to-do Quaker family in Philadelphia, Hannah Griffitts wrote poetry throughout the revolutionary period which hailed moderation and condemned extremism from both Patriots and Loyalists. Indicting Paine as a "Snake beneath the Grass," she grieves that moderate political voices are no longer

Articles and news, personal stories, interviews with experts.

Photos from events, contest for the best costume, videos from master classes.

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |